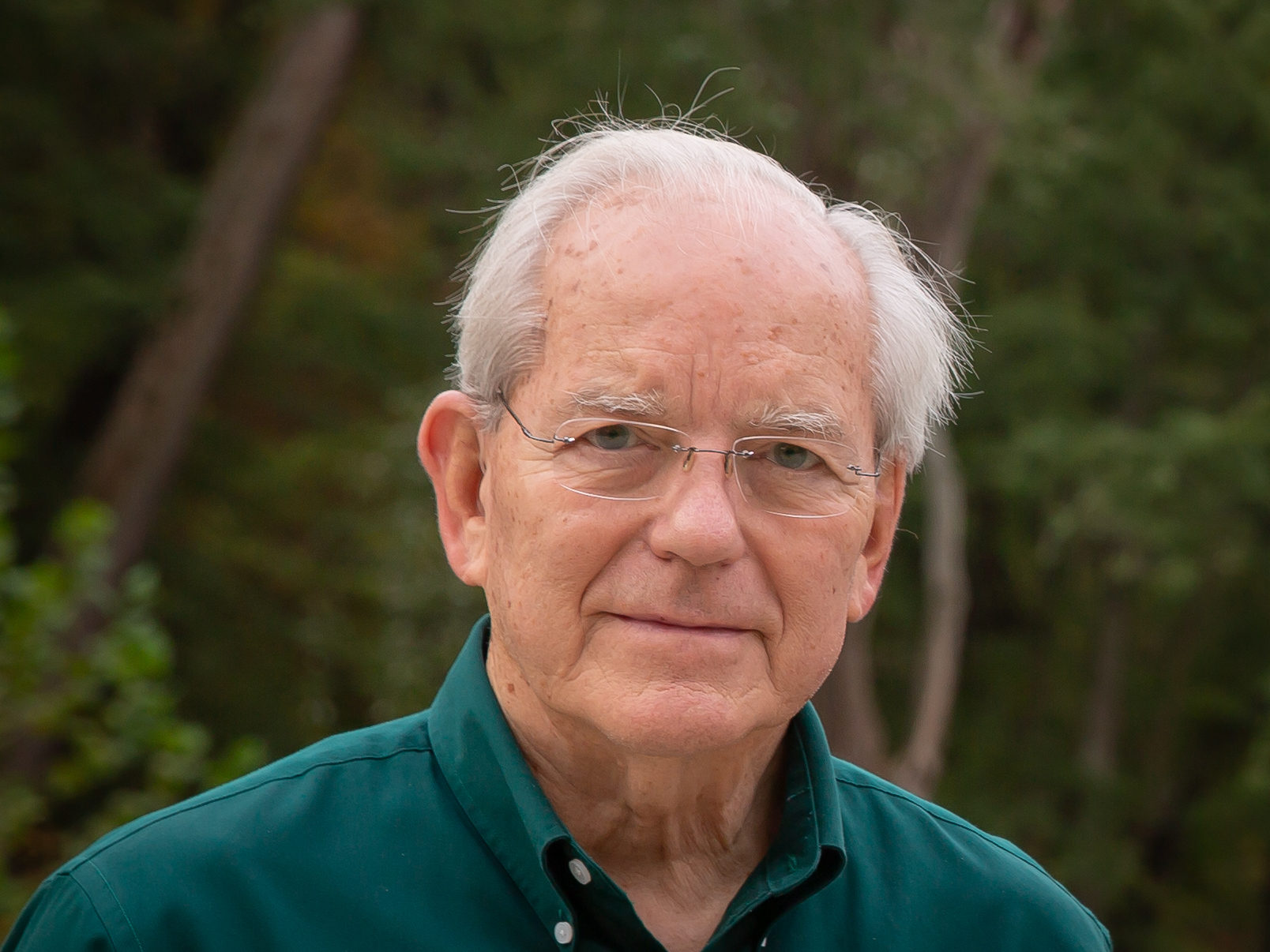

It is with profound sadness that we share news of the passing of Prairie Rivers Network’s founding father, Dr. Bruce Hannon. Bruce’s accomplishments are too numerous to recount in full, but among other things, he was a distinguished Professor Emeritus of Geography, an environmental visionary, a community leader, an expert clocksmith, a beloved husband, father, grandfather and great grandfather, and a deeply kind and generous man who never stopped working to make this place better for all who live here.

Bruce dedicated his life to fostering environmental consciousness and protecting Illinois’ natural treasures, including Allerton Park and the Middle Fork of the Vermilion River. His passion for advocacy led him to found multiple organizations including The Committee on Allerton Park (later becoming Prairie Rivers Network) and The Land Conservation Foundation. Through his tireless efforts, he nurtured a sense of place among the community, instilling in new generations the great responsibility of environmental stewardship. All of us who spend time in and appreciate Illinois’ rivers, woods, prairies, and natural landscapes owe a great debt to Bruce Hannon and his wife, Patricia, who passed on in 2022.

Bruce’s legacy is one of enduring inspiration. His teachings, values, and the organizations he founded will continue to guide those who take up his mantle and work at building a society and culture that respects and coexists with the natural world. As we mourn his passing, let us also celebrate a life well-lived, a life that left an indelible mark on the landscape and hearts of those who were fortunate enough to learn from and stand alongside this remarkable man.

Remembrances

by Clark Bullard

Bruce Hannon changed my life. As we walked through the UI quad on the first Earth Day, 1970, we noticed that most pollution was caused by energy use: digging it from the ground, burning it in the air, or spilling it on the way back from Alaska. As engineers, we observed that using half as much energy could solve half the nation’s environmental problems.

Bruce got a grant to analyze the energy needed for throwaway cans vs. refillable bottles, and I spent a summer during grad to help write a broader proposal. I began to think of alternatives to my planned career in the Los Angeles aerospace industry where I had worked during previous summers.

The moment of decision came one night while standing in the shower. I asked myself how did I ever get mixed up with this Hannon guy? We had just returned from a visit to Commonwealth Edison’s new headquarters building in Chicago, where we tried to explain to two executives that they had built an energy hog, using horribly inefficient technologies for heating, insulation, etc. The senior engineers in their Brooks Brothers suits understood how conservation threatened electricity sales. They responded in the harshest most condescending way possible. Telling me, a PhD student in aerospace engineering, to get back in my lane.

But our numbers were right. The building was causing twice as much environmental harm as necessary. I had spoken truth to power, and power barked back. Bruce said it’s ok. I was about to get married and planning to have children. I thought of the quotation that Bruce put on the letterhead of his Committee on Allerton Park: This generation will decide if something untrammeled and free remains as testimony for those who follow. The decision was made – standing in the shower.

There was no turning back, no regrets. What followed were decades of learning. As academic engineers we formed an interdisciplinary team of computer scientists, psychologists and labor economists. Together we developed the methodology for calculating the ‘energy footprint’ and ‘carbon footprint’ of hundreds of goods and services. But most important is what I learned from Bruce as a role model: how to organize diverse coalition of citizens, to communicate with voters, to speak truth to power and endure the threats and personal attacks that came with the territory.

My friendship with Bruce was a gift that kept on giving. I treasure that relationship every time I enjoy the Middle Fork River, especially on those birthday campouts with each of my three children.

by Eric Freyfogle

For the past twenty-five years I have labored to convert my sizeable, south Urbana lawn into a woodland, as much of it as I can. My efforts have been sporadic and I’d have more to show for them if I had started with clearer vision. Many of my young trees are volunteers—sweet gums, redbuds, black cherries, a fast-rising tulip. In the front, a red maple and river birch stand tall, but the six native cedars in the back are hardly chest high.

Most striking, as one surveys my tract, is the prevalence here of oaks. A mature pin oak, predating my tenure, shades my south-facing roof. Joining it now are nine other oaks of varied ages, eight burs and one white. All came from a single source, a source that for decades supplied thousands of bur oak seedlings (and the occasional white oak sprout) free of charge to landowners around the twin cities. The seedings arrived with advice on planting and pruning. They arrived also with a friendly, contagious enthusiasm for regreening the land. I wonder: Will there be, a century from now, attentive observers who speculate on the cause for so many prairie oaks in shady local yards?

My bur oak spouts grew from acorns shed by trees around the Harding Band Building, or so Bruce Hannon told me. He collected them, tended them in UI greenhouses over the first winter, and then put them up for adoption (as he termed it) by the hundred. Bruce asked recipients to keep him informed of the progress of his bountiful Quercus progeny. I hope many did so. My communications were regrettably few, mostly reports on three early trees that now reach the canopy. I wish I had given Bruce a fuller accounting. He deserved to know what he was leaving behind.

For a man remembered for starting organizations Bruce Hannon really had little interest in institutions as such, in their operations and functioning. By-laws, rules of order, and the like were mostly distractions. An organization for him was a just handy mechanism for bringing people together and arousing their interest; it was a rallying point, a venue for scheming and celebrating. The environment needed people to stand up for it if it was going to gain and retain health—that truth Bruce knew in his core. And for decades he recruited for the cause, sharing his love of nature, seeking (as he confessed) to make environmentalists out of unsuspecting citizens. Often the aim was to save a part of nature under threat, like the wooded grove along Urbana’s Lincoln Avenue, just south of Jimmy John’s, which campus planners slated for a new building. That campaign brought success, as did many others. But defeats came, too. Despite an incredible door-to-door petition drive led by John Thompson and Bruce—one that likely collected more signatures than any such drive in county history—local officials refused to replace the county’s last landfill with a new state-of-the art one. Their choice instead was to ship the county’s solid waste to less-safe facilities elsewhere, with county residents footing the continuing bills for the lengthy, polluting truck drives.

By the 1980s and 1990s environmental clashes were becoming more technical and legally complex. Many came framed around lengthy statutes and regulations. They required, to provide meaningful citizen input, scientific knowledge that ordinary citizens lacked. While people could still attend public hearings, their comments counted for little unless focused on the precise issues at stake, often procedural matters tangential to core questions of policy. As Bruce’s Committee on Allerton Park evolved by stages into Prairie Rivers Network, its conservation work was increasingly and necessarily performed by professional staff, who struggled to find ways for ordinary members to help.

Bruce recognized the inevitability of this shift, the declining effectiveness of his beloved, halt-the-reservoir model. But he would insist that people still needed arousing; they still needed connecting with nature; ordinary citizens still needed to become environmentalists. And so as PRN’s scientific and legal staff took up the more technically and legally confined challenges, Bruce sought out new opportunities to bring people together, new settings in which he could share his enthusiasm and continue his community-growing efforts. There was always, for instance, natural lands to conserve and restore through direct citizen action. And for him personally there were, every fall like clockwork, acorns to collect, clean, and turn into seedlings, ready for planting in early spring.

In my case, Bruce’s final message arrived four days before his death. Here is what is going on, he said. Here is what we are trying to do. Can you help?