Gulf of Mexico’s 4th smallest “Dead Zone” since 1985

By Catie Gregg

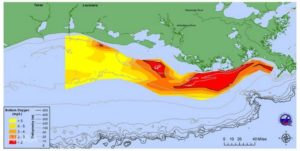

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released the results of their summer mapping of the Gulf of Mexico hypoxic zone. This year they forecasted an average-sized hypoxic zone (5,780 sq mi) in May based on the nutrient load coming down the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers. However, when they measured the actual size in July, it was much smaller than expected at 2,720 sq mi. They believe this was due to the heavy winds seen right before and during the mapping which pushed the hypoxic zone into a smaller area and in some areas increased the oxygen mixing into the water.

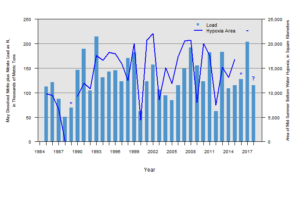

Even without wind distortion, this year’s hypoxic zone would have been significantly smaller than last year’s. Last year, we saw the largest hypoxic zone in the Gulf to date at 8,776 sq mi. So does this mean we are making progress on our nutrient reduction goals or is it just normal variation due to weather?

What does this mean?

While year to year variation in the size of the hypoxic zone is mostly related to the weather that year, there has been about a 13% reduction in nitrate loads and a 10% increase in phosphorus loads to the Gulf. According to U of I researcher, Greg McIsaac, “Flow-normalized nitrate loads to the Gulf of Mexico declined slightly in the mid-1980s and have been fairly steady since, while flow-normalized loads of phosphorus have increased since about the mid-1990s.” Illinois has seen similar changes in its river nutrient loads with a 10% reduction in nitrate and a 17% increase in phosphorus. These decreases in nitrate loads are thought to mainly be the result of increased fertilizer efficiency by crops and perhaps changes in Chicago’s nitrate discharge over that time period.

How does this impact to Illinois’ Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy?

Illinois and other states in the Mississippi River Basin have been asked by the Gulf of Mexico Hypoxia Task Force of the U.S. EPA to reduce the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus exiting their states by 45% by 2045. This is expected to reduce the Gulf hypoxic zone to a 5-year average of less than 5,000 sq mi. To meet these goals, Illinois developed the Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy (NLRS). The NLRS has only been in effect since 2011. While Illinois’ 10% decrease in nutrient loads gets us a little closer to our 45% reduction goal, it needs to be taken with a grain of salt. The majority of this reduction occurred before the NLRS started, and a 10% reduction in nitrate over almost 40 years won’t get us to a 45% reduction by 2045.

Furthermore, phosphorus loss is increasing. Some researchers point to the expansion of no-till farming, a key conservation practice, as the source of this increase. No-till improves soil structure and leaves more residue on the surface to protect the soil, both of which reduce soil loss. However, when phosphorus fertilizer is applied in a no-till system, it stays closer to the surface than if it was incorporated with tillage. As a results, we see less soil loss, but the soil that does leave the field may have higher levels of phosphorus attached to it. It is important that we continue to evaluate the impact of new practices so that we can learn and adjust them as necessary. For example, combining cover crops with no-till can further reduce phosphorus in runoff while amplifying the soil health benefits. It is often the case that multiple practices are needed to create a system to reach our soil health and nutrient goals.

Reducing the size of the Gulf hypoxic zone is a monumental task which will change agriculture as we know it. And change is hard. This is especially the case when there are very limited additional resources available to accomplish this goal. Nutrient pollution affects millions of Americans, not only through a lack of oxygen for Gulf fisheries, but in harmful algal blooms that affect our swimming lakes and streams, and in elevated levels of nitrate contaminating our drinking water. This is a problem that is worth solving and one in which we should invest resources.

We have seen hundreds of farmers and landowners change their farms, and wastewater treatment plant operators take steps to reduce the nutrient pollution flowing from their facilities. Yet, it is not enough. We will need conservation activities on every acre, and urban as well as rural participation to reach our goals for both local water and the Gulf.

It is easy to get burned out on a long term goal like this. It can’t always feel urgent. We must continue to push forward even as we make progress to get back the clean water that we depend on.