We appreciate that the State of Illinois has undertaken the process of revising the State Water Plan. This is a critical moment in the state’s history in regards to the future of our water resources. Climate change is already altering weather patterns and precipitation. Water supplies are stressed in parts of the state. Many of the state’s waters continue to be fouled by agricultural and industrial pollution decades after the passage of the Clean Water Act. The state’s plan needs to address the various threats and issues of the 21st century to ensure that the state has plentiful clean water to sustain the health and well being of all the people of Illinois, as well as the health and functioning of its natural systems, its wildlife, and its lakes, rivers, and aquifers.

Summary Comments

Many of the recommendations in the plan call for new or more studies, increased agency funding, and public outreach and education. These are actions that are often needed, but for certain issue areas, the plan is relatively light on actions that would substantively address the problems that have been identified. Perhaps, without further study and data collection and analysis, this is all that is practicable at this stage. If so, the State Water Plan should be blunt and honest about this reality. Yes, the plan acknowledges that it provides a 7-year focus strategic plan and calls for regular updates, but the plan should make clear how preliminary this document and process is in terms of both diagnoses and prescriptions.

Comments on Individual Sections

Water Challenges (3-5, 3-6)

Here “climate change” is described as a changing trend. Little mention is made throughout the plan of the anthropogenic nature of climate change. That climate change is largely a function of human-caused emissions should be addressed more directly throughout the plan as there are serious implications both for mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The definition provided for “Illinois Water Use Laws and Regulations” is far too expansive. This section, as in the 1984 plan, should focus on water use and withdrawals, rather than “any issues pertaining to water legislation and administrative rules,” which is clearly so broad as to be functionally meaningless. Indeed, this subcommittee did end up focusing its work and recommendations on water use, and the description used here should reflect that.

Water Quality

On 5-2, the plan reads:

great strides have been taken over the past four to five decades to reduce both point and nonpoint sources of pollution from impairing our surface waters. . . Implementation of numerous voluntary or incentive-based programs have all served to keeping millions of tons of nitrogen, phosphorus, sediments, and other nonpoint source pollutants on the landscape and out of Illinois rivers and the Gulf of Mexico.

We strongly object to framing the issue of, in particular, non-point source pollution as one in which substantial progress has been made. This is unacceptable and misleading. As the most recent Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy report made clear, nutrient loading in Illinois’ rivers and streams

is getting worse, not better. For all the millions of tons of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other pollutants that have been kept out of surface waters due to implementation of voluntary programs, even more pollutants have entered those very same waters. As the plan notes, primary contact uses do not meet Clean Water Act interim goals in 89% of streams, and fish advisories exist on most waters assessed in the state. This should be the top line message of the Water Quality section, not misleading statements about “success.” Illinois has a surface water quality problem due to the impact of runoff.

Little is actually said about the state of groundwater quality. Prairie Rivers Network urges the state to undertake a comprehensive, statewide groundwater quality survey capable of identifying the extent of contamination in most if not all aquifers being used for drinking.

The plan mentions that the state has undertaken PFAS testing, but there are no details as to the results of those tests. A recent article in the Chicago Tribune revealed that the majority of Illinoisans are getting their drinking water from a utility where PFAS have been detected. This should be addressed in the plan.

Water Quality Recommendations

- There is no indication that Illinois is going to meet its goals for the Illinois Nutrient Loss Reduction Strategy. In fact, the evidence shows the state to be going backwards. This should be acknowledged. Any recommendations concerning the INLRS need to offer a viable pathway for the INLRS to be effective. The State Water Plan should address what will happen if and when the INLRS goals are not met, as is likely. More than funding is needed for the INLRS, serious commitments must be made by the state.

- If voluntary measures are not working, as they haven’t been, the state needs to discuss other options to reduce pollution, particularly non point source agricultural pollution.

- The state should undertake a comprehensive, statewide groundwater survey.

- There is not enough focus on the issue of nitrates in shallow drinking water wells. The state should undertake a study to determine the full scope of the problem and educate well owners about the dangers of nitrate in shallow wells. We recommend considering requiring inspections at the time of sale of property with wells, much like is done for termite inspections.

- The nitrate drinking water standard (10mg/L) is too high.

- Funding for monitoring and understanding of Harmful Algal Blooms in Illinois waters should be increased, not just maintained. The current program only monitors a few water bodies and is not able to give us an overall understanding of the issue in our state. This is especially critical for water bodies that are used for drinking water. We recommend a credible sampling program with publicly posted results for each waterbody that is open for public access.

- The IDOA nitrate and pesticide monitoring network needs to start testing for nitrate again, with those tests encompassing a broader network of wells than in the past. The current network concentrates monitoring wells in only a few geographic areas of the state. While some of the network’s monitoring wells have not found high nitrate levels in certain areas, other studies contradict these results, finding high nitrate levels in those same areas. More well testing over a broader area would provide a more accurate assessment of nitrate levels. Additionally there needs to be a review of the pesticides the network tests for. Pesticide use has changed over the past two decades and the list of pesticides the monitoring networks tests for should be expanded.

- Furthermore, because this network uses modern drilled wells it cannot represent the water quality of older wide bore dug wells. Previous reports in Illinois have found dug wells to have a 60% chance of being over the safe drinking water standard for nitrate. Illinois’ groundwater monitoring program needs to be applicable to our most vulnerable wells and the residents who depend on them. This will require a statewide survey of drinking wells for nitrate and pesticides with enough detail to identify these additional nitrate hotspot.

- EPA should work with IDPH on water quality programs for private well owners. Funding water quality testing and outreach grants for county DPH offices is an option to do this. As mentioned above, requiring testing at time of sale should be considered.

- The Illinois agronomy handbook needs to update the manure application recommendations. Currently, rates that supply 3 times the amount of phosphorus that should be applied to a crop are allowed. This encourages overapplication of phosphorus when fertilizing cropland with manure. Penalties should be issued for overapplication.

- Soil and Water Conservation Districts (SWCDs) need funding to reach out directly to the individual farmers in their district. Much of their current funding focuses on field days and managing contracts applying to conservation programs. These approaches wait for farmers to show interest in their programs. Voluntary programs don’t have to be passive. However, often staff have so much paperwork to do they don’t have time to do the time intensive direct outreach which can be some of the most impactful ways for reaching farmers. Providing funding which requests SWCD staff to do more direct outreach with their farmers will allow them the time to create the relationships and trust necessary for farmers to take a chance on trying a conservation practice.

- There is no mention of pesticides in surface, ground, and/or treated drinking water. USGS and IEPA have been finding pesticides, their adjuvants, and metabolites in water for decades. They reach waterbodies through runoff, spray drift, and atmospheric deposition of vapor drift. Recent studies have also detected them in rainfall. The active ingredients, adjuvants, and the metabolites of pesticides such as atrazine, alachlor, glyphosate, neonicotinoids, and others have been found widely in waterbodies. Many pesticides, particularly if they are water soluble or are known to bind to sediments, can increase in surface waters during rainfall events or can remain in sediments for extended periods of time. We mentioned this in past comments but the plan does not reflect those comments. Pesticides are a serious water quality problem and the plan should acknowledge them. Pesticides, like other water contaminants, are a serious environmental justice issue as poor and rural communities suffer disproportionate harm but often lack the funds to inform citizens, prevent pollution, and/or clean up water resources. If this plan is to take environmental justice seriously, pesticides must be addressed.

- As for point source pollution, there is no mention of coal mines, coal ash, or coal plants. A 2018 analysis of industry data found 22 of 24 coal fired power plants had impacted groundwater with coal ash leachate. Abandoned mine lands, often a source of acid mine drainage, are also not mentioned in the plan but should be.

- CAFOs are also not discussed as a likely source of water pollution.

Lake Michigan

The Lake Michigan diversion is generally treated as a benefit for the state of Illinois, which is understandable. But what is not mentioned is that Lake Michigan water quality standards are higher than Chicago River water quality standards, which means that Chicago can treat its waste to a lesser extent than it requires for its drinking water source. And that waste gets sent to downstream communities. This is itself, an environmental justice and equity issue that has long been glossed over. Downstream communities, whether Joliet, Peoria, or East St. Louis, all receive wastewater that is treated to a lesser extent than is acceptable for Lake Michigan. The State Water Plan should acknowledge this and entertain ways to remedy the inequity and injustice, starting with upstream sewer bills funding downstream water plants.

In 10-3, the plan describes maritime transportation via the CAWS as “underutilized.” We object to this blanket statement. Shipping on the CAWS has been in decline for decades. See this NRDC study. It is unclear whether millions or perhaps even billions spent on upgrading port and lock and dam infrastructure would lead to an increase in shipping that would warrant the expense, or whether declines in maritime shipping are a function of external economic factors unrelated to the condition of transportation infrastructure. At the very least, the State Water Plan should provide a balanced analysis of the costs and benefits of shipping, rather than assuming it is a net benefit. The costs should include the massive amounts of public subsidies that are dedicated to shipping infrastructure as well as the attendant environmental harms caused by managing rivers largely for the benefit of shipping.

Climate Change

As mentioned above, the plan does not directly discuss climate change as a function of human behavior and human-caused emissions.

The State Water Plan should at least mention that, while climate change is a global problem with global causes, Illinois must do its part to mitigate climate change, in addition to adopting the various recommendations here that would provide useful adaptation to climate change.

Missing from the Plan is a discussion of how climate change is likely to impact food production outside of Illinois and what that might portend for food production in Illinois, including possible increased pressures on water resources in the state, in particular with regard to water quality (resulting from even more intensive agriculture) and water quantity (water withdrawals used for agriculture).

The Plan mentions that Illinois may experience shorter, but more intense periods of drought. The Plan should address what this could mean for the future of irrigation in Illinois and how increased irrigation would impact water supplies throughout the state.

Climate change can also impact the presence and prevalence of certain pesticides in waterbodies. Certain herbicides readily volatilize at higher temperatures and drift to non-target lands and waters. Increased temperatures and humidity are likely to contribute to this phenomenon. Additionally, increased rain events and their associated sediment loss is likely to carry more pesticides that bind to soil into waterbodies. This, along with the threat of pesticides generally, should be discussed by the Plan.

The recommendations for the Climate Change section largely amount to improved information distribution and more research. Perhaps we do not yet understand what our adaptation strategies need to be, but there needs to be a path to get to implementable strategies for climate adaptation as quickly as possible.

Flooding

The state should study which levees are doing more harm than good for preventing flooding.

Habitat

In Illinois’ overwhelmingly modified landscape, rivers and streams provide some of the best-remaining wildlife habitat. This fact could be even more prominent. It is good that the Plan discusses connectivity, but we would recommend that this section coordinate with Climate Change to address how habitat will be impacted and to examine how rivers and streams can serve as migration corridors for wildlife stressed by climate change.

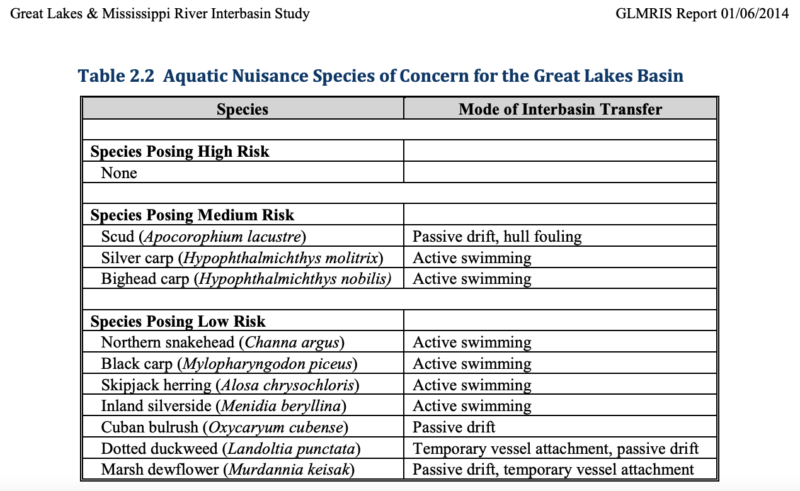

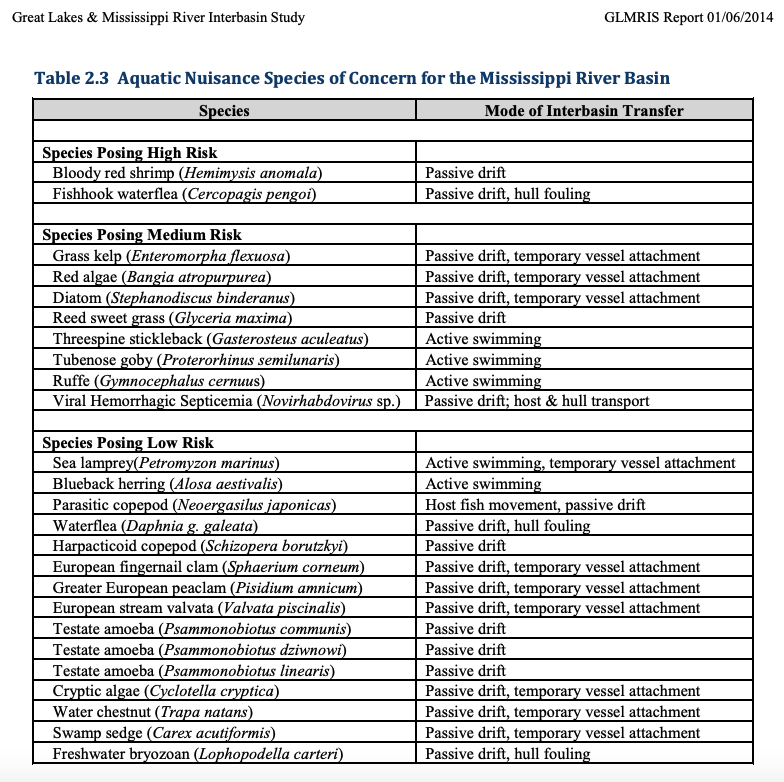

The Army Corps of Engineers in its Great Lakes Mississippi River Interbasin Study identified dozens of aquatic invasive species (AIS) that threaten to move between the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins. The vast majority of these species are currently in the Great Lakes

threatening to enter Illinois’ rivers (see the chart below from the GLMRIS report). 10 species were identified to be as great or more of a threat ecologically and economically as invasive carp. While millions of dollars are spent every year on invasive carp, little is being done to address these other AIS. The plan should recommend that comprehensive surveys be done, updating the list of aquatic invasive species that might threaten Illinois’ waters, and that solutions be developed for the full range of AIS, preventing their transfer in both directions between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River basin.

The state must be aware of likely changes coming at the federal level due to future Supreme Court Rulings and take a proactive approach, in particular with regard to enacating strong state level wetlands protections.

Water Use Laws and Regulations

It is helpful that this section refers back to the 1984 Water Plan and gives details on the recommendations from that plan that were or were not completed. In particular, we recommend that implementation of minimum flow standards be an outcome of this latest Plan.

Recreation

As this section also discusses Aquatic Invasive Species, please see our comments on AIS in the habitat section above.

The state should do a thorough review of the law regarding public access to rivers and streams throughout the state.

The public should have access for paddling recreation in all waters that are navigable under federal law and all”public waters” as defined by Illinois law. IDNR should recognize that under the River, Lakes and Streams Act at 615 ILCS 5/18:

Wherever the terms public waters or public bodies of water are used or referred to in this Act, they mean all open public streams and lakes capable of being navigated by water craft, in whole or in part, for commercial uses and purposes, and all lakes, rivers, and streams which in their natural condition were capable of being improved and made navigable, or that are connected with or discharged their waters into navigable lakes or rivers within, or upon the borders of the State of Illinois, together with all bayous, sloughs, backwaters, and submerged lands that are open to the main channel or body of water and directly accessible thereto.

Environmental Justice

18-13 lists maintenance of port and lock and dam infrastructure as a social and environmental justice issue. We object to this classification. Not coincidentally, navigation infrastructure often is situated in areas of the state that suffer the most from environmental burdens and environmental injustice. No rationale was given for inclusion of these items as contributing to social and environmental justice. They should be removed from this table.